How hard is it to buck demand curves?

Like, can you have a high-priced product that’s also a high-volume product?

It’s one of the oldest truisms in business: if you raise your prices, demand (and thus volume) should go down. It’s the ‘Demand Curve’. Augustin Cournot described the relationship in 1838 (20 years before the invention of the oil well).

But now that we have zillabits of data, does it hold up? Why yes, it holds up remarkably well.

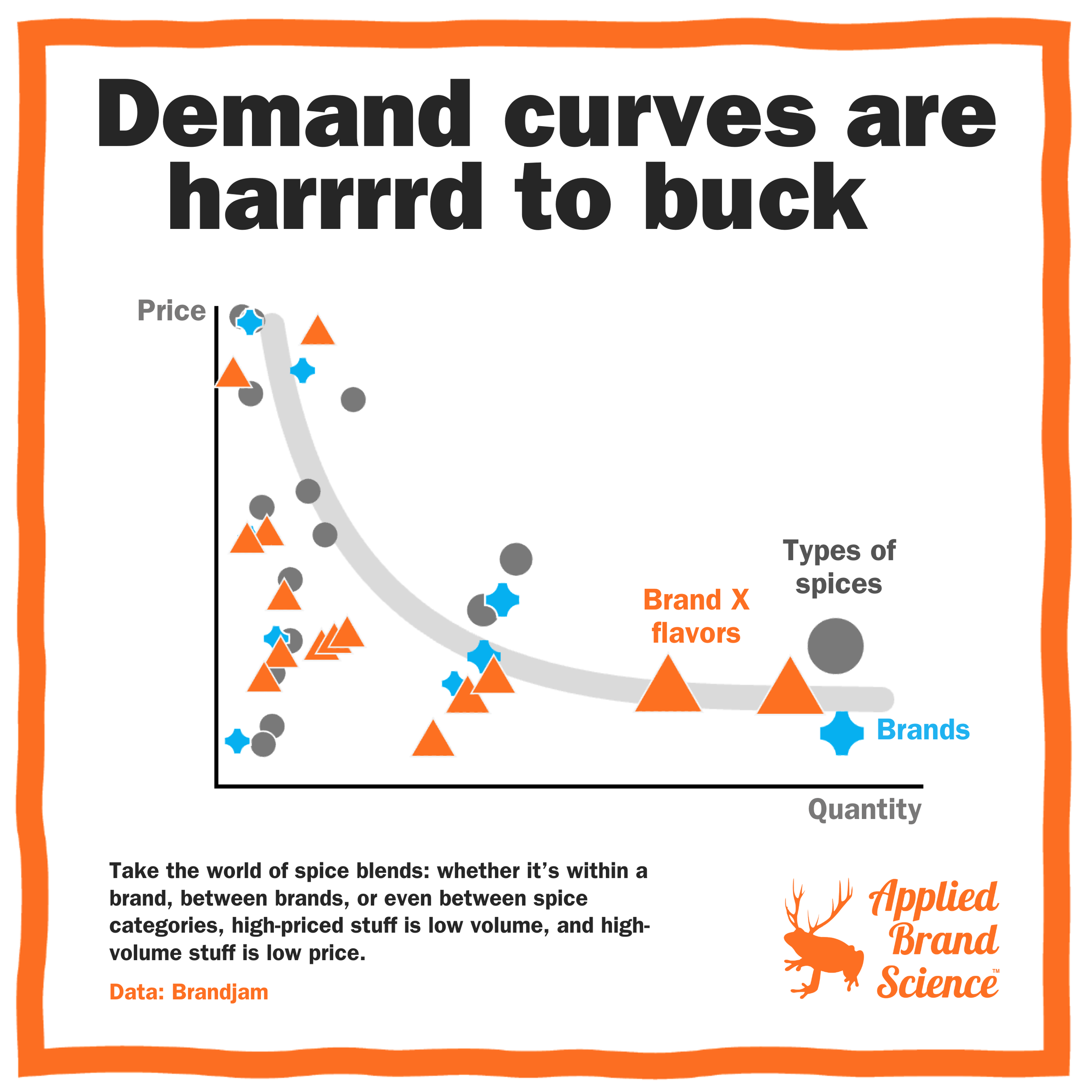

F’rinstance, in the world of spice blends (you know: Mrs. Dash, or Old Bay, or Taco seasoning), you see the demand curve play out at multiple levels:

🧂 Expensive blend types (stuff with cloves or saffron) sell less, while high-volume types (grill rubs) are low-priced.

🧂 Expensive brands (Traeger, Dan-O’s) sell less, while high-volume brands (Baida!) are low-priced.

🧂 Expensive flavors (garlic truffle) sell less, while high-volume flavors (steakhouse, all-purpose) are low-priced.

[Nerd detour: something that shows up at all scales is a fractal. I studied fractals in ecosystems in grad school.]

Does low price guarantee high volume? Absolutely not. But high price almost guarantees low volume. It’s the classic trade-off, and the choice depends on manymanymany other things: strategy, margins,market position, market history, etc etc etc.

The demand curve is so common, in fact, we could call it a law.

Are there some deviations and exceptions? Tune in next week. Would those deviations prove the law ‘wrong’? Nope. There’s always a platypus (look them up: they’re weird AF), but that doesn’t ‘disprove’ laws about mammals or marsupials.

Some lessons:

🍊 Assume the Demand Curve is a law of nature.

🍊 Assume you won’t create a high-price product that’s also the category volume leader.

🍊 Tune in next week when we talk about brand platypi.