Do “purpose-driven brands” really perform better?

Like, does having a higher purpose, or social purpose, improve your brand’s financial performance

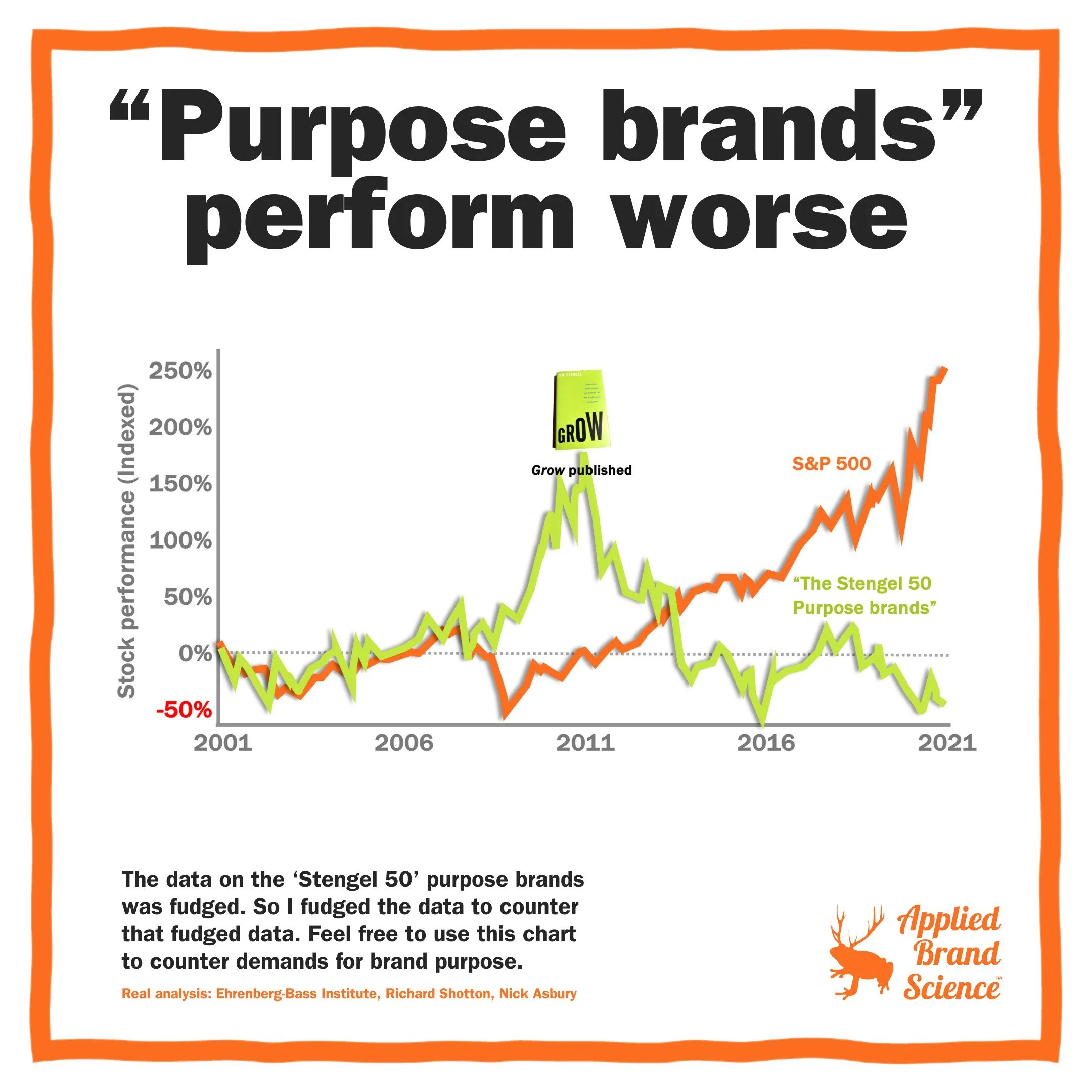

This is an idea that was brought to its zenith in Jim Stengel’s 2011 book “Grow: How Ideals Power Growth and Profit at the World's Greatest Companies.” And it has held immense sway in the world of marketing ever since.

What’s the brand purpose of your mayonnaise? Why does your SaaS procurement software rilly rilly rilly exist? How is your deck stain making the world better? (Aside from, you know, helping you stain your deck.)

But there’s a problem. Well — two. No, actually, more like 4 or 5. Big ones. Methodological ones and empirical ones and, well, really, they all roll back into One Big Problem: it’s just plain wrong. It’s bad data and bad science and a bad conclusion.

Richard Shotton did a brilliant take-down of GROW. The Ehrenberg-Bass Institute also skewered its glaringly-weak methods. And recently, Nick Asbury might’ve put the final nail in the coffin. I won’t repeat them.

And rather than fight fire with water, I figured I’d fight fudge with fudge.

Since GROW fudged a bunch of stuff, I just fudged this chart (the green line, at least). Note, tho: I only made up the precise curve: in truth, only like 13 of the “Stengel 50” brands continued to out-perform the market after 2011.

Some lessons:

🍊 Real science is harrrrrrd.

🍊 Question the data — the actual original data. Are you measuring what you think you are?

🍊 Don’t believe purpose is The Way To Grow. It ain’t.