Do luxury brands play by different rules?

[This week is a longer post, done in partnership with Tracksuit, the brand tracking company. Read it here or read it over on the Tracksuit Blog.]

Luxury brands: what are they anyway? Do they behave like shampoo and noodles, or are they categorically different? Do they follow the laws of every other brand, or do they float in space like bricks don’t? Are they defying gravity, or can we pull them down? What’s the deal with luxury brands

We can’t answer all those questions here. But we can look at some tantalizing data on who buys them and how they compete to see if it’s anything like other categories, or if it’s a world apart — “a world of luxury beyond your wildest dreams….” Let’s start with who’s buying luxuriously.

BRAND BUYERS

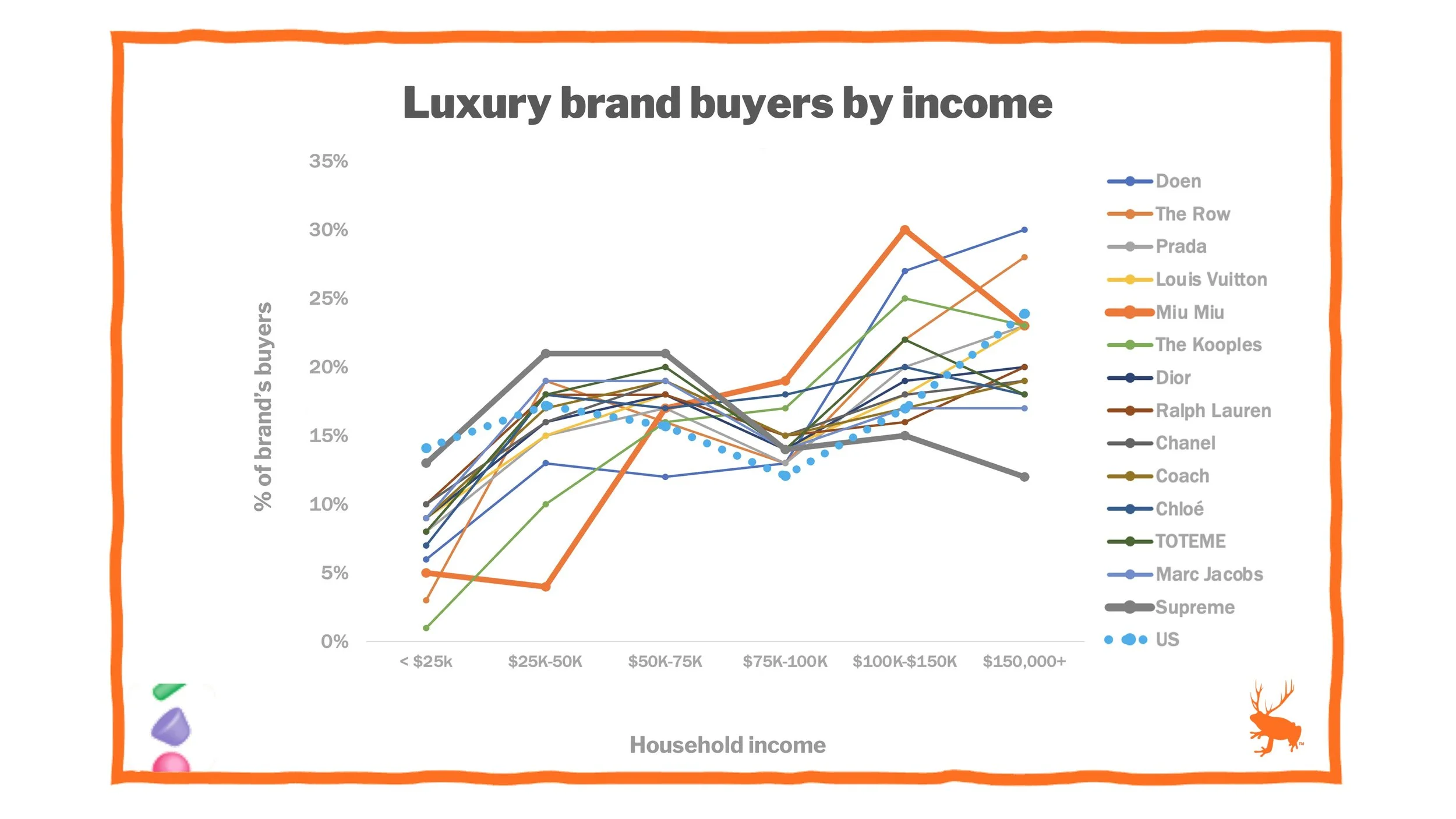

The chart below shows who’s buying some major luxury brands in the US, broken out by household income (HHI). Some things that are predictable pop out of this chart:

For most luxury brands, higher-income households make up the bulk of their buyers, and low-income households are less common (mostly less than 10%). Indeed, these brands have fewer buyers at the low HHI range than exist in the US population (the blue dotted line). They skew wealthy — as expected.

Brands known to be more expensive (like Miu Miu, the orange line) are bought by wealthier households than brands known to be more ‘street’ (like Supreme, the gray line).

The brands show some variation — what I very technically call “wiggle”. We often expect brands to have different fingerprints for stuff like this. In this case, the sample size is well over 4,000 people, so the wiggle is very likely to be real and not just an error from sampling.

But some things become evident that are perhaps counterintuitive:

A good 5% of luxury brand buyers (ish) are making less than $25K a year. Another 10% to 20% are only making $25K-50K. Add the third income bracket, and roughly a third of luxury brands’ buyers are from these lower-income homes. A third! That, to me, seems surprisingly high. But the desire to get good products (or products that say something about you) knows no economic bound.

Speaking of, buyers of these brands generally track the distribution of wealth in the country (the blue dotted line) above $25K. We tend to think luxury is for the rich. But this data shows that the whole population buys luxury brands, regardless of their income. Granted, this is binary on/off data, so if you only own a single silk Prada scarf, you count as a Prada buyer (and a suave person, too). It’s likely wealthier households buy more luxury products than others — though it would be good to check the numbers.

As for the wiggle, why do the brands wiggle the way they do? F’rinstance, why do Dôen & Prada have a higher proportion of wealthy buyers, whereas Marc Jacobs & TOTEME have fewer? We’d have to dig deeper to understand. But the data points us in the right direction for good questions.

BRAND IMAGERY

There’s a divide in the brand science world about whether brand imagery really matters to the success of a brand. On one hand, some smart folks say that brands compete mainly by holding different ‘positions’ in people’s minds, and that brands must feel different to win, even if they are functionally very similar. On the other hand, some brainy people say that brand image doesn’t have much of an impact on the business, and that brands are quite interchangeable in the grand scheme of things.

This varies significantly by category too. Certain things where products are quite comparable and features have mostly been copied are more commodified or interchangeable (e.g., toothpaste, pipe fittings.) Others still show more difference between brands (e.g., clothing, jewelry.)

Specific attributes play smaller or larger roles in purchase decisions too — they’re category drivers or purchase drivers. Tracksuit shows which attributes are more important purchase drivers.

However, the first question, a priori, must be this: do luxury brands actually have different brand images? Why yes, yes they do. Especially among those who know them.

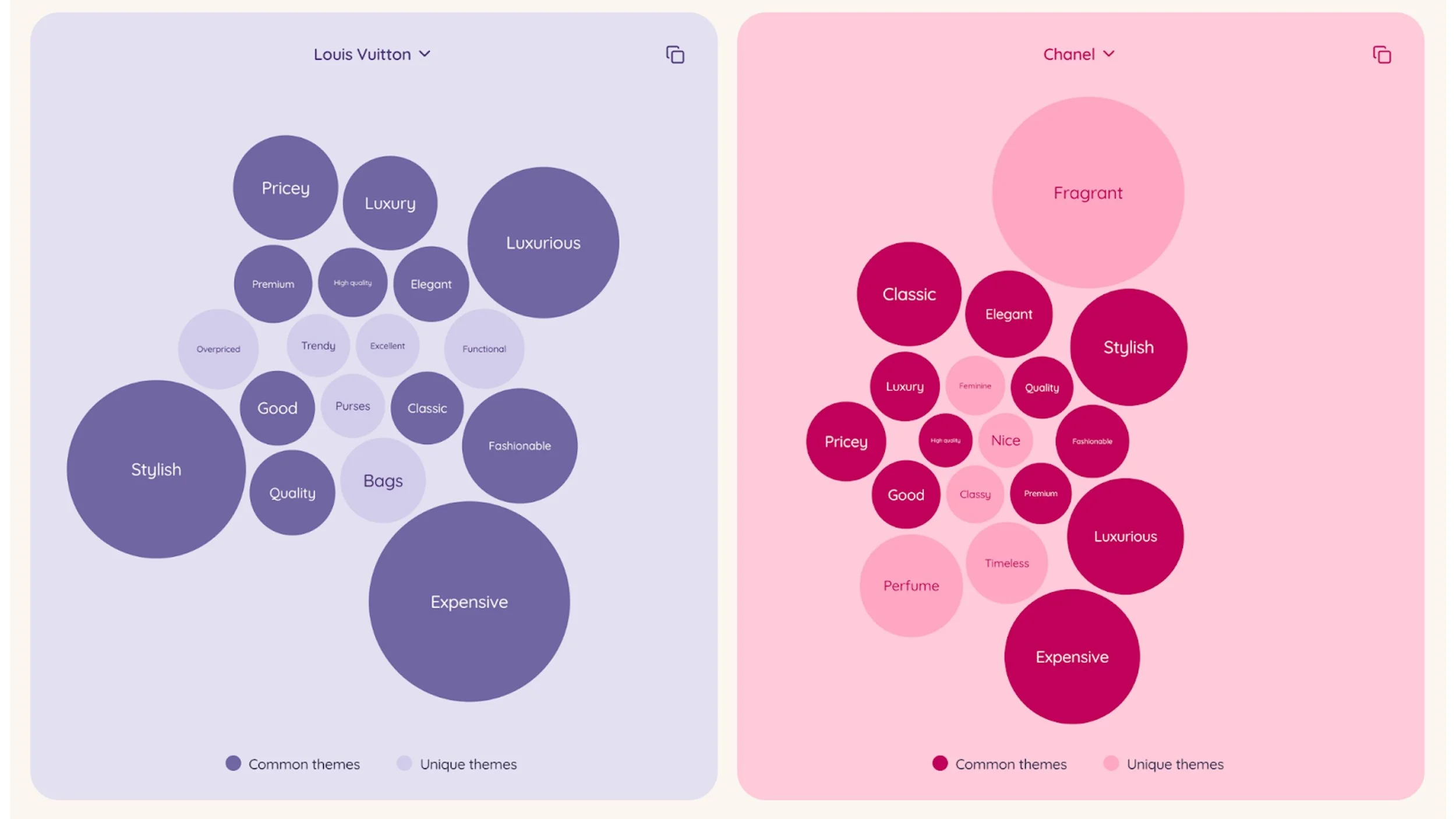

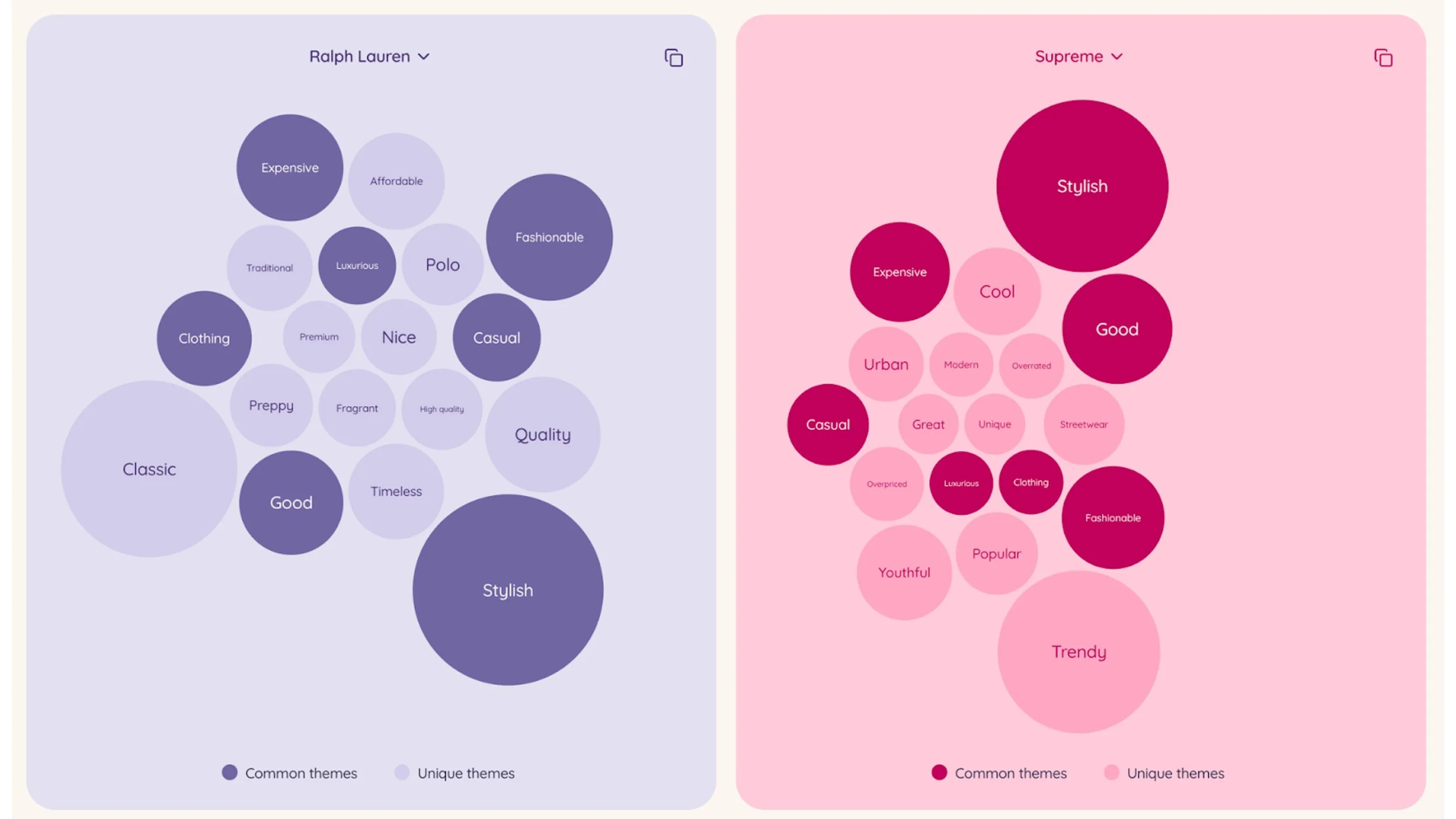

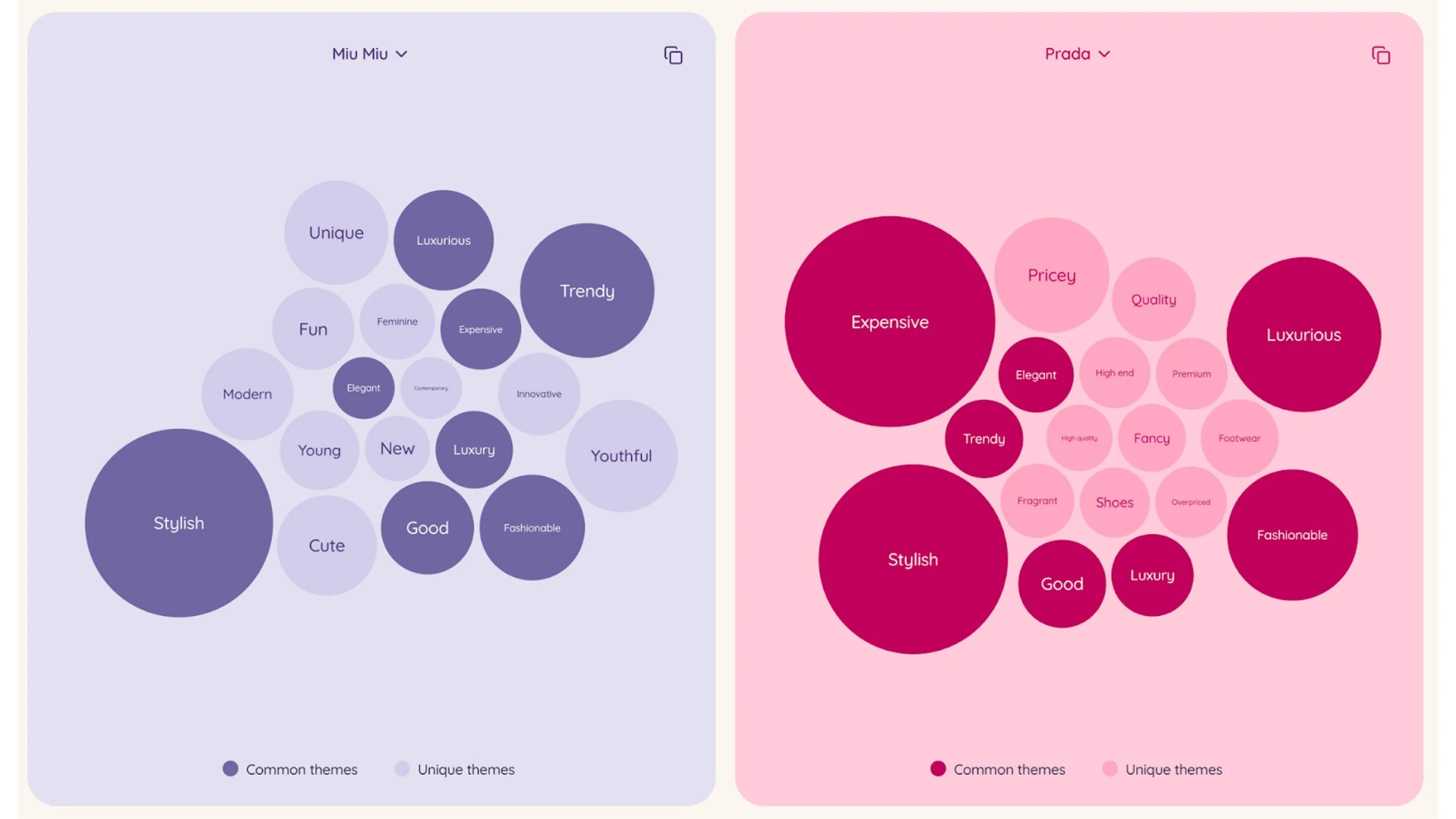

Below are pairwise comparisons for a few luxury brands. Each image shows what the brands have in common (dark circles) and how they differ (light circles). Circle size shows how often that attribute came up for the brand.

Are brands 100%, categorically different? Of course not. But across 20 or 30 factors, they have degrees, and some strong fingerprints.

F’rinstance, here are two classic French fashion brands: Louis Vuitton, founded 1854; and Chanel, founded in 1910. We’d think these two old stalwarts would be quite similar. And it’s true. Things in common: expensive, stylish, luxurious, classic, good, quality, pricey, elegant. That sounds right. But there are indeed things that are different: LV is seen as bags, purses, trendy, functional, and overpriced; whereas Chanel has a huuuge image of fragrant, plus perfume, timeless, classy, and, to a lesser extent, feminine. That checks out intuitively, what with all that famous Chanel perfume and the enduring reputation of Coco Chanel herself. So both intellectual camps would find something to cheer here. “See? They overlap a lot!” “Yes, but they’re different too!”

Here’s another comparison, between Ralph Lauren (1967) & Supreme (1994). This time, we’d assume they’d have more differences. And it’s true. They are both seen as stylish, expensive, fashionable and casual. But Ralph Lauren is classic, timeless, polo & preppy; whereas Supreme is (very) trendy, youthful, urban, cool, and streetwear. These images check out intuitively too. Again, both camps would have support.

One more, for fun: Miu Miu (1993) vs. its parent, Prada (1913). This one’s fun because Miu Miu was launched specifically to be a younger, more experimental, more playful line than stately old Prada. Here we can ask the data, is it working? Both are stylish, expensive, luxurious, fashionable, elegant, & trendy. That’s good. But whereas Prada is pricey, fancy, footwear and fragrant; Miu Miu is youthful, cute, young, new, unique, modern, feminine & new. As far as imagery goes, mission accomplished, I’d say.

So luxury brands do indeed have different images. Sometimes of degrees, and sometimes categorically. Just like other categories, which isn’t a shock.

Data like these help you see if your brand is “on brand”: is it portraying what you want? Is the imagery what you’d hoped? Are there negative connotations you’re trying to avoid? And as I’ve written about previously, it’s vital to ask these questions of all category shoppers, not just your avid admirers or freakiest fans.

CATEGORY STRUCTURE

There’s another thing we can learn about the luxury category by looking at fundamental brand tracking data: whether the category is structured like others, or whether it somehow defies brand physics.

See, nearly every category follows some basic law-like patterns. One of the strongest patterns, first observed in the 1960s, is that big brands have more buyers and higher repeat purchase. While lots of marketers believe there are some small brands with crazy-high repeat rates (aka loyalty), these “little passion brands” don’t seem to exist in the real world. This pattern is called ‘Double Jeopardy’, since small brands suffer twice (few buyers & lower repeat purchasing). But it could just as well be called ‘The Tyranny Of Size’, because brand size also predicts a range of other factors: scores on brand attributes, awareness, share of search, and so on.

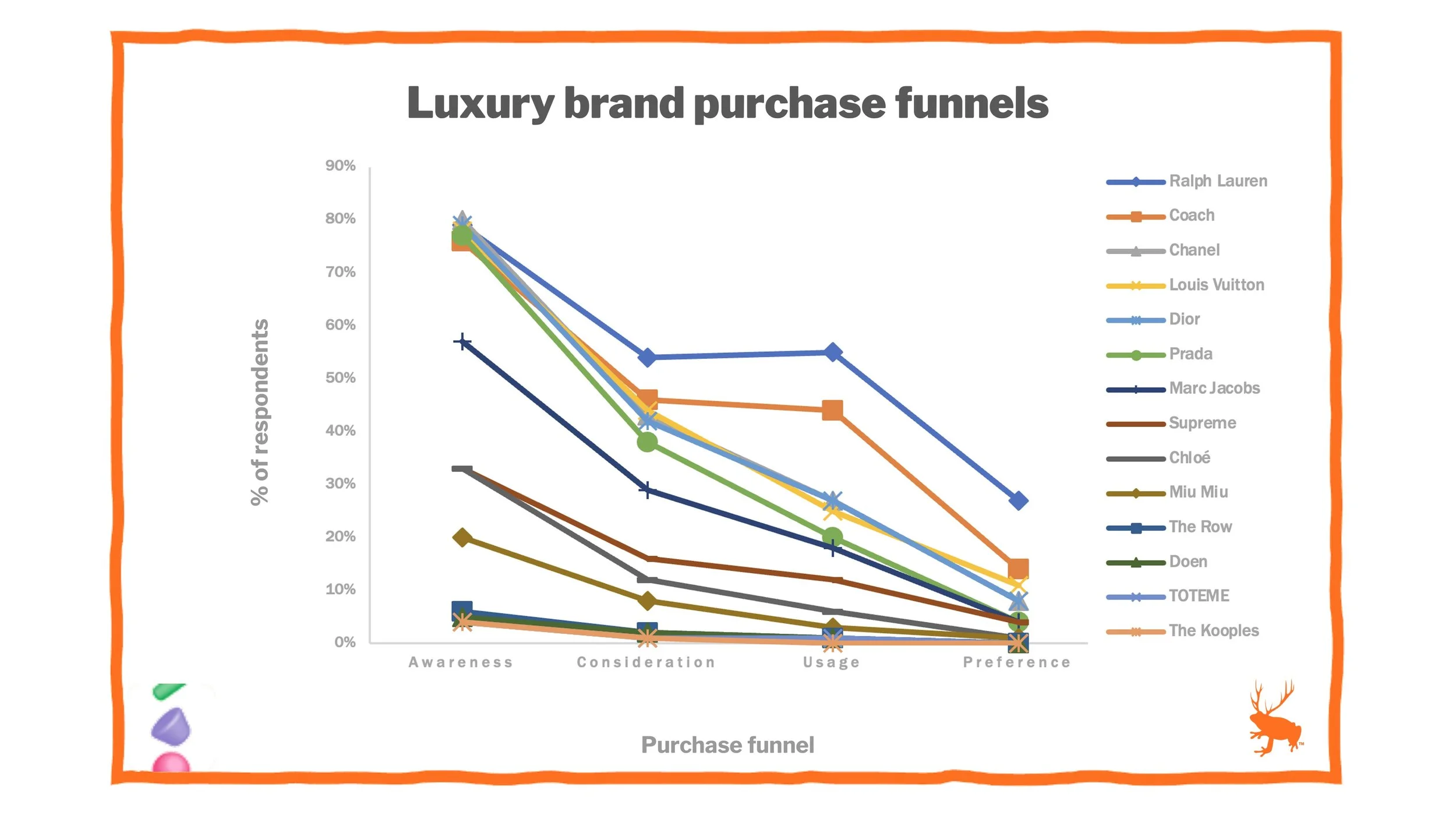

So what about purchase funnels? Given the laws of brand science, we’d expect that large brands have higher scores for all purchase funnel metrics, and small brands have lower scores. We’d also expect a little wiggle, but we’d need other data to explain it.

So do we see these patterns in the luxury category? Below is a chart showing the purchase funnel for these same dozen-ish brands in the U.S. from mid-2025. And sure enough, large brands like Ralph Lauren & Coach & LV have bigger funnels, and smaller brands like TOTEME & The Kooples have smaller funnels. (We don’t have all the revenue for each brand, or revenue broken out by brand for those from larger companies. But it seems to generally track.)

We also see that there’s some wiggle. F’rinstance, Ralph Lauren & Coach have a big bump in usage vs the rest of their funnel. Prada’s & LV’s usage are a bit lower than expected. And Chloe’s awareness is a bit higher than expected. This wiggle of course then leads to the question of why. These data can’t answer that, but without the funnel, you wouldn’t even know where to start looking.

THE SAME, AND MAYBE NOT

So from the perspective of brand tracking data, luxury brands show lots of the same patterns we’d expect from shampoo and noodles. They don’t seem to defy the laws of brand physics. They’re bought by a range of consumers in ways that aren’t far off from the population. They have both similarities and differences in brand images. And they show evidence of Double Jeopardy.

Other data do indeed show ways in which luxury brands behave differently than noodles. (Search for “Veblen Goods” and “costly signaling theory” to start on that journey.) But at least from high-quality brand tracking data, luxury brands, as they say, are “just like us, but rich” :-) .